All of us at Nothing Over Ten have a sort of funny infatuation with the amazing photographer Robert Doisneau! Even Google is honoring him today:) You go Google!

If you don’t know much about him, here’s an essay and some pics to fill you in:) ***Warning this essay will make you want to visit Paris… ENJOY!!!

( *To reprint or obtain publishing permissions please email: ContactNothingOverTen@Gmail.com )

==================================================================

Robert Doisneau’s Jocund Fiction

Robert Doisneau’s black and white photography captures an undeniable sense of nostalgia. His romanticized shots of Paris and its players are most often light hearted, loving, humorous, and reflect a youthful like wonder and innocence. These iconic shots add to the global allure of Paris. Like a teenage dream, his photos montage themselves inside the head of the modern day world, washing it with a visual poetry that we long to feel. His most famous and stylistically representative shots were taken between the tumultuous years of 1930-1960. His airy sentimentality during these three decades of fear, upheaval, reform, and artistic growth, reflect a need to capture those fleeting moments of happiness amid the incomprehensible cruelties forever found in humanity. In a way, Doisneau begs Paris to smile and say cheese, and with these directed moments of fragmented life, we find, once again, hope.

French photographer, Robert Doisneau was born April 14, 1912, just two years before the onset of WWI. His artistic training began as young boy, where he studied engraving. Later in life, the attention to details, and compositional framing necessary for engravings would become an integral tool in his career as a photographer, where he was in large part self taught (Hamilton 1992). After losing his father in WWI and his mother at the young age of seven, his early life, according to his daughters, was plagued with sadness and lack of love (Follain 2005). At the onset of World War II, he was drafted into the French army where he was used as a soldier and a photographer (Cooper n.d.). How the war and his innocence depriving upbringing truly affected him, is difficult to quantify. After his death in 1994, his daughter Francine said, “He never showed his sadness to us. He would come into the room and you immediately felt that everything would be fine, and fun (Follain 2005).”

While Doisneau’s photographs are widely loved, they are not given as much artistic merit as his friend and Alliance Photo Agency brother, Henri Cartier-Bresson. Doisneau is more like the Norman Rockwell of France. His work is easy to understand, depicts idyllic everyday lifestyles, is rated PG-13, and tongue-and-cheeky in humor. In general, prints that make you say, “Ahhh, how cute!” and are easily marketable for mediums like postcards, coffee table books, and calendars. Or, at least, that’s what they appear to be at first glance. Using a more photographic eye, a much more dynamic story is told through his lens. Doisneau said he did not appreciate “monstrous images made with an impatient desire to be original (Ollier 1996).” So, what did he appreciate and what made him original?

Robert Doisneau’s Le Plongeur du Pont d’Iena (Fig. 1) is a photograph shot in Paris in 1945, less than one year after the city was liberated from German control in August of 1944. The Pont d’Iena crosses over the Seine river (Jigourel, Pozzoli and Rizzi 2005). His low camera angle gives the foreground a fearful and surreal perspective. Doisneau’s timing captures the diver, spread eagle, and flying over the river while the onlookers far below stagger the famous steps, as the most iconic of all city icons, the Eiffel tower, for once is outshined. The viewer does not know why they are jumping, or if it’s safe. The young boys upon the ledge share the overall emotion of the scene. Some appear to be amazed, some scared, some feigning bravery, some matured and tough, but all apart, and transfixed in this moment, as is the viewer. While the shot can be read as young boys at play, it can also be seen as a “decisive moment” of liberation and a symbol for the resilient nature of the French people to regain their joy after the nightmare.

Fig. 1: Robert Doisneau. Le Plongeur du Pont d’Iena. Paris. 1945.

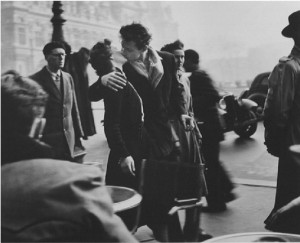

Robert Doisneau’s most famous photograph is undeniably, Le Baiser de l’Hotel de Ville (Fig. 2), shot in 1950. This photo was commissioned by LIFE magazine, and according to Doisneau’s first extensive biographer, “sums up all the romance and allure of Paris and the French (Hamilton 1992).” The article in LIFE described Paris as a place where unabashed couples “seek out parks or deserted streets for their romancing (Hamilton 1992).” The two young lovers were actually actors that Doisneau set up all around the city and directed them to kiss in various places, including in middle of traffic, like two performing artists making a scene in front of unaware onlookers. If you look closely at their kiss in front of Hotel de Ville, the power of this shot comes from Doisneau’s over the shoulder point of view, which gives the viewer an entryway into the scene and allows them to feel like they are voyeuristically watching the kissing couple. The people walking by them, have an appearance like they notice what is going on, but are unaffected and walk on. Or, they feel uncomfortable by the intimacy, and continue walking, intentionally ignoring them. The shot appears candid, another skill of Doisneau. The “authenticity” of the shot was extremely important to LIFE, but for Doisneau, the importance comes from the message it sends to the longing eyes of the viewer. The romance that we desire to have, is what he captures, and breaks the fourth wall of our maturity, and tells us it’s possible, and more importantly, important. Or, in his own words, “I don’t photograph life as it is, but life as I would like it to be,” he said (Follain 2005).

Fig. 2: Robert Doisneau. Le Baiser de l’Hotel de Ville. 1950.

In Doisneau’s, Le Dame Indignee (1948), we see the photographer’s sense of humor. Once again, he ingeniously hides himself as the photographer, and creates a hidden vantage point where the viewer is able to safely shield themselves and observe the tableau without participation. The slap stick reaction of shock plastered on the old women’s face, as her bug eyes are glued to the rear end of the naked woman in the photograph, parallels our reaction, which is in turn mirrors the reaction of the woman passing by on the street. The visual connection he creates, while the shot itself may be comical in tone, reflects Doisneau’s compositional achievement as well as his paramount skill in pictorial story telling.

Robert Doisneau. Le Dame Indignee. 1948.

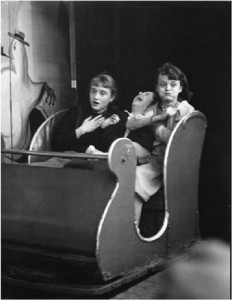

In Train Fantome, we find Robert Doisneau’s favorite theme and subject; the innocence of youth. Here we see three young girls all experiencing the same moment, and yet all having different reactions. The fear, hysterics, and relief seen in their faces capture a once in lifetime moment. The next time they ride the Phantom Train, it won’t be the same; the innocence of the experience is gone forever. Doisneau uses the camera as the medium to capture this idea, and without words, which so many authors have devoted to this theme, reveals this universal state of being, in a timeless still. This subject of visual poetry, that he continues to create throughout his career, may be a clue to how his own loss of innocence, where the world losses much of its magic, affected him, and how he longs to bring it back for himself, as well as for others, stirring a joyful imagination in a world so plagued by sorrows.

Robert Doisneau. Train Fantome. April 1953.

For Robert Doisneau, the camera was a filter, that “in those ordinary surroundings which were (his) own…glimpsed some fragments of time where the everyday world appeared to be freed of its ugliness (Hamilton 1992).” In some ways, it’s more difficult to show the pretty. Doisneau struggled to get these happy shots. He worked to see the optimism in the world and reveal it to those who have forgotten it exists. Knowing this he said, “To show such moments could take a whole lifetime (Hamilton 1992).” While he may have manufactured a jocund fiction in his humanist reporting during the lifetime of his work, without his contribution weighing in as a hopeful counterpoint for the world’s recollective memory, those trivial moments of everyday joy, that make up our lives, would have been lost forever. In this way, Robert Doisneau belongs in our canon of artistic photographic education.