Art Critique: Alberto Giacometti – The in Between

*To reprint or obtain publishing permissions please email: ContactNothingOverTen@Gmail.com

==================================================================

December 1, 2010

The In Between

“God is absence. God is the solitude of man (Jean-Paul Sartre).”

“The older I grow, the more I find myself alone (Alberto Giacometti).”

It’s a Sunday in Las Vegas. I’m late. My mistake of taking Las Vegas Boulevard requires a deep breath to smother my frustration. Traffic is stopped. The sidewalks teeter with tourists, and an overwhelming feeling of claustrophobia hits me, as my eyes dart from generic eye catching images to alluring false advertisements. My phone rings, and I can’t find it in my purse. I hear another beep indicating a voice mail, and another, signaling a text. I’m shifting gears with my elbow, and steering with my knee. Can’t I be left alone for just one afternoon? I wish I could close my eyes and make the chaos go away! Finally, I arrive at the Bellagio, valet park my car, and rush inside the faux Italian villa. I pass the overpriced shops, ignore the flashy slots, and don’t even glance at the tables. After what feels like a short eternity, I reach the Gallery of Fine Art.

Museum’s are, and always have been, my personal place of Zen. However, actually studying art is a new pursuit. Up until now, I’d never gone into a museum with a particular aim, concept of expectations, or even desire to see a particular artist. Most of the time, I never even read the titles. What I have always done is go alone, and wander at my own rate, taking from my experience something new each time, and always leaving with a relaxed resolution, and a new question about the reality I exist in. In these silent dialogues with art, my random thoughts, that are most often too convoluted for elocution, are given an audience, as my exhausted rational mind is awarded a must needed rest. But, to study art, unfortunately requires both sides of my brain to be present.

Today’s exhibition is Figuratively Speaking: A Survey of the Human Form. My assignment is to find a twentieth century artist, actively working before 1960, gaze upon their work and be inspired enough to write, what is for me, a dreaded research paper. The Gallery is small, especially when I compare it to last summer’s trip to the Louvre and Uffizi. I stand just inside the entrance, waiting for the tour to commence. I never took one tour in Europe and now I’m taking a tour in a room probably smaller than the size of the Vatican’s janitor closet. People surround me, yet, while still being in a quasi museum, my place of sanctuary, I find a happy sense of anonymity, and disregard for anyone else in the room.

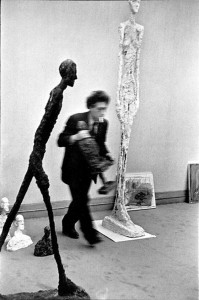

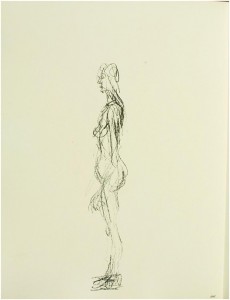

I read the introductory exhibit description, mildly bored, imagining what an awesome job the curator for the Bellagio must have. It must be nice having a huge budget and very small expectations. The only goal of this place is to add more prestige to the casino. The majority of work comes from MGM Mirage’s bastard collection. Some literally ripped off the ways of a now defunct restaurant. The human form must be such a difficult subject to find material for! Breaking my sarcastic thoughts, the obnoxious vibrate setting on my phone, throws me back to the now. Pulling it out of my purse, I answer it in an annoyed hushed voice, and walk away from the gathering crowd to the corner on my right, suddenly aware I’m not invisible. It’s my niece. She’s ten and finds no objection in calling me until I answer. How adorable and obnoxious. In the sweetest voice I can whisper, I tell her I will in fact be there for Thanksgiving, and that I’ll talk to her later. This time I turn off my phone completely, return it to the abyss known as my purse, look up, and placarded directly before me is a Giacometti (Fig.1).

Fig. 1: Alberto Giacometti. Untitled, illustration 141, in the book Paris sans fin by Alberto Giacometti (published in 1969). c. 1957-1962

Elongated black lines, roughly sketch the paper, shaping a “human form.” This central, undressed, standing figure is depicted with a disproportionate round belly and bottom, skinny legs, exaggerated fingers, and giant-like arms that almost reach its knees. At first glance, it is difficult to determine if this sketch is a man or a woman. Its body is more like a Mr. Potato Head that you can attach different attributes to. Depth is present, but it is difficult to ascertain a point of view because there is nothing in the foreground or the background. There are no other figures in the sketch, but why do I get the sense she’s (had to make the executive gender decision) not alone?

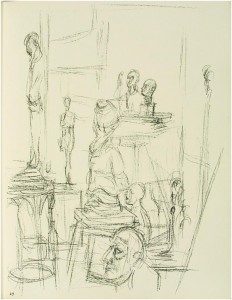

Next to this sketch is another by Giacometti (Fig. 2). In this one, the scene appears to be an artist’s studio, filled with busts and full length statues. Seated in the middle of the frame, is what appears to be, at first glance, a female model with her back turned to us, her hair in a loose bun. In the bottom foreground is a side profile of a man’s head, but given the surrounding sculptures, and the way Giacometti drew this, it’s impossible to know if he is real or crafted. This forces a reevaluation of the picture as a whole, and the “female model” suddenly loses its truth. “She” has no arms or legs, it is just a bust. The crude quality of the image illustrates how the mind fills in and colors the voids, creating values that don’t exist. There’s nothing real in a sketch, but the sketch, and yet, I want to see life in the drawing. I want to see an artist with a model in his studio, not just inanimate sculptures in a depth defying space. I replay my day in my mind, and realize this is the first time I’ve really seen anything. Everything else today has just been a blur of accepted reality based on previous experiences and associations that lend themselves to quick, rational explanations. I return my gaze to the fist image of the solitary woman and the strangest sense of…random thoughts take over, too quickly for my mind to sort. As my right brain quickly takes control, and I continue to stare at her with relaxed eyes, it occurs to me why she’s not alone.

Fig. 2: Alberto Giacometti. Untitled, illustration 29, in the book Paris sans fin by Alberto Giacometti (Published in 1969). c. 1957-1962.

“Umm, excuse me ma’am. Ma’am?”

I hate being called “ma’am.” Guess I’m getting old. I turn away from the Giacometti’s to see a crowd staring at me.

“We’re starting the tour now.”

Oh, yeah, the tour. I’d almost forgotten. I have to find a topic for my research paper.

We walked around the big room, discussing Degas, Renoir, Picasso, Close, and Voila… but there was no magic decisive moment. Amazing pieces, but I didn’t get that feeling of artistic destiny. I walked around one more time, and came back to those crude sketches that had pulled me down their vortex. The solitary woman stands profile, her bug eyes staring into the nothingness in front of her. I feel almost voyeuristic peering at her, trying to unravel her enigmatic quality. This is why I like art, because no matter how hard I try, words never seem to do it justice.

I reluctantly leave. With Giacometti still on my mind, I think of the song Nights in White Satin, by The Moody Blues. That eerie, distant sound, and uncommon flute solo, has an atmospheric sense of nostalgia and mystery, with a odd lyrical epitaphic poem at the end which says, “Cold hearted orb That rules the night, Removes the colors From our sight, Red is gray and Yellow white, But we decide Which is right And Which is an Illusion.” This sort of resembles how Giacometti’s work made me feel.

Arriving home, I decide to research Alberto Giacometti for some answers to my intrigue. He was born at the turn of the century, during the industrial revolution on October 10, 1901 in the Italian speaking area of Switzerland. His father, Giovanni was a post-impressionistic painter. He began drawing at a very young age. One prophetic story was his problem with drawing pears in his father’s studio as a child. Instead of drawing them in scale perspective, he continued to depict them as they appeared in reality. The further away the pears, the smaller he drew them. This phenomenological (depicting things how they are) existentialist (viewing human life from the internal perspective) artistic execution would become a common thread in his work (Lord 1986, 33). He is both “painter and sculptor (Lanchner 2001).” Between 1927 and 1934, he began working with the surrealist artists, including Andre Breton (Fletcher n.d.). In 1935, he is accused of surrealist disloyalty by depicting realistic images of his brother Diego and his sister Rita. In 1937 he befriends existentialist fiction writer, Samuel Beckett, whom he later designs a tree for his infamous play, waiting for Godo. In 1939 existentialist philosopher, Jean-Paul Sartre introduces himself to Alberto in Paris, and later writes a famous essay, “The Search for the Absolute,” on Giacometti’s mature, signatory work (Fig. 3), displayed in the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York in 1948 (Hohl 2001). His iconic style is elongated human statues that make it impossible to determine a sense of perception because even up close, his work appears to be far away. In Sartre’s philosophy and in this essay, I find my answers.

Fig. 3: Alberto Giacometti. City Square. 1948. MoMA.

Sartre discusses Giacometti’s visual existential philosophical impact on the viewer. He says, “(Giacometti) has to write movement into the total immobility, unity into the infinite multiplicity, the absolute into the purely relative, the future into the eternally present, the chatter of signs into the obstinate silence of things (Sartre 1965).” My entire day had been this chatter. It wasn’t until I confronted his work that I found reflective silence. In this silence, this commune with the sublime, I realize now the reason the woman in his sketch didn’t appear to be alone is because I became a participant in her world. I became as false to his sketch, as she becomes real in my mind. Sartre describes this Giacometti phenomenon, “there seems to be an unbridgeable chasm; yet the chasm exists for us only because Giacometti took hold of it. I do not know if we should regard him as a man who wants to impose a human stamp on space, or as a rock about to dream of the human. Or rather, he is the one and the other, and the mediation between them (Sartre 1965).” So, in this chasm, in this abyss, in this absence we find truth, or as Sartre would say, we find god.

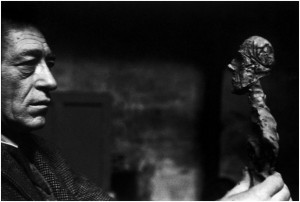

Giacometti depicts the void that we often ignore and forces us to see. In his deconstructed sculptures (Fig. 4) and in his drawings, we see an isolated reality. But, isolation for Giacometti isn’t a good or bad thing; it’s just a state of flux between what we perceive and what we don’t. For Giacometti, the interconnectivity between what is illusion, human, or inanimate, our brains deem the same. While our intellectual mind evolves and expands, our inner intimacy with our world grows and becomes more difficult to explain, thus becoming more isolated within the barriers of our mind and the limitations of communication. Giacometti finds a way to bridge this and communicate a universal voice that fills an unspeakable void within the world.

Fig. 4: Alberto Giacometti. Walking Man. c. 1960

Bibliography

Fletcher, Valerie J. “Giacometti.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T032017pg3 (accessed November 27, 2010).

Hohl, Reinhold. “Alberto Giacometti: Chronology.” MOMA Interactive Exhibitions. 2001. http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2001/giacometti/start/pdfs/Giacometti_Chronology.pdf (accessed November 15, 2010).

Lanchner, Carolyn. “Alberto Giacometti: Painter and Sculptor.” MOMA 4, no. 7 (September 2001): 6-9.

Lord, James. Giacometti: A Biography. New York: Frarrer, Straus, and Giroux, 1986.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. “The Quest for the Absolute.” In Philosophy of Existentialism: Selected Essays, by Various, 388. New York: Philosophical Library, 1965.